A fastener must be tight enough to do its job. But what is tight enough? What would happen if a bolt broke or the nut came off? Consider the cost of failure-anywhere from minor property damage to major loss of life or equipment. Tightness is important, but it is equally important to know how tight and to ensure the accuracy of a torque wrench measurement.

Every joint has a minimum tightness. Below this point, the joint may come apart in service either by working loose or by bolt breakage.

There also is an upper value of torque beyond which the bolt can break when tightening. This upper value likely will be reached after the bolt has been in service for a length of time. Removal torque cannot be used as a guide; it is different than installation torque.

Some bolts do not require as much care as other bolts because of their design or manufacturing process. Joints using soft fasteners, such as Grade 2 bolts, yield before breaking. On the other hand, there are many high-strength alloy fasteners that do not have much give before failure. These fasteners cannot compensate for being misapplied.

Some joints have been carefully designed to save weight, such as those used in aerospace applications or those designed specifically to save cost in mass production. Joints not designed around weight requirements usually are stronger than they need to be, giving the operator considerable latitude.

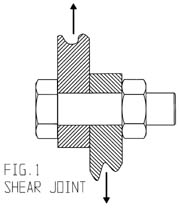

With a shear joint, the forces acting on the bolt are perpendicular to the bolt. Source: Wright Tool Co.

Loading

To understand how fasteners work, it is necessary to understand the different types of loading. With a shear joint, the forces acting on the bolt are perpendicular to the bolt. These tend to cut the bolt by shear rather than stretch it.

Most structural bolts are shear. For example, the joints between horizontal beams and vertical columns are shear joints. Tightening torque is not essential to the operation of the bolt, but the tension developed from tightening may be the only thing holding the joint together. The exact amount of tightening torque required depends on the length of the bolt, among other factors. But, a reasonable amount of extra tightening torque does no harm.

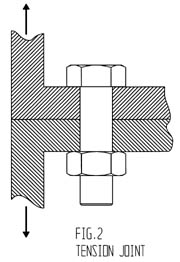

Tension loading tends to stretch the bolt, and tightening torque plays a significant role. Automotive and aerospace joints are usually either tension or mixed joints. If a tightening torque is specified, it should be followed.

A third type of loading is a combination of tension and shear. These bolts should be tightened like tension joints.

Tension loading tends to stretch the bolt. Source: Wright Tool Co.

Bolt tightness

The amount of tension required for a bolt depends on the size and grade of the bolt, as well as the nature of the load. Also, a safety factor should be included to provide for unexpected conditions.

Pre-tension is the amount of tension or torque applied to the bolt in installation. Because bolt tension is difficult to measure, bolts must be tightened to a torque. The relationship between tension and torque depends on factors such as lubrication, finish and accuracy of thread forms. These factors add an additional source of variation.

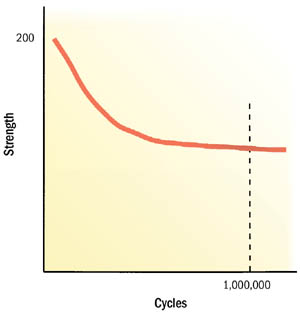

Fatigue is a property of steel. If the steel has the strength of 200,000 pounds per square inch for a single load application, it will carry this load indefinitely at room temperature. If the load varies, it can fail if the peak load is as low as 100,000 pounds per square inch. It can take as much as a million cycles for this failure to happen, or it may be just a few cycles, depending on how close the maximum is to the ultimate strength and the percentage of variation. If the steel fails from a simple case of overloading, fastener failure will occur the first time it is loaded, or possibly during the tightening.

Failure from over-tightening can either be immediate or delayed, tempting some to tighten less than specified to ensure that such failure does not happen.

One purpose of tightening a fastener is to provide enough clamp load so that the bolt or nut does not work loose because of vibration, but there is a greater danger. Fasteners normally hold a joint together so there is positive clamping pressure under all conditions and fluctuations of load.

Most joints have flanges or other contact areas between the mating parts. Initially, these carry the same load as the bolt preload, but where the bolt is in tension, the flange is in compression.

With a 1,000-pound pre-load on the bolt, there is a 1,000-pound clamping force on the flange. If the dynamic tension load does not exceed 1,000 pounds, everything works fine.

Dynamic load is more critical and potentially damaging than preload because it is applied to the structure instead of to the bolt. It is shared by the structure, and only a small part of the dynamic load is transferred to the bolt. But, if the structure is separated, the bolt takes the full amount of the fluctuation. As severe fatigue sets in, failure is likely.

Is too loose better than too tight? For a tension joint or a joint that is a combination of tension and shear, neither state is acceptable. In some cases, too loose can be significantly worse than too tight. If the preload is not sufficient and the joint separates under the working load, the bolt becomes more exposed to fluctuations in the applied load.

If the applied load is a cyclic load, the bolt is exposed to substantial fluctuations in tension, which may cause fatigue failure. This would not have occurred if the preload had been sufficient to keep the joint from separating. This does not mean that the bolt should be over-tightened to avoid this condition; over-tightening also can cause failure, but it will take somewhat longer to occur.

For correctly tightened bolts that are breaking, use higher strength bolts, larger bolts or more bolts with the appropriate tightening torque for the new bolts.

When bolts are replaced with stronger bolts of either the same size or larger, they must be tightened to at least the torque that was specified for the joint. This prevents an overloading problem but will not prevent failure if the joint separates under working conditions. It is better to increase the torque in proportion to the change in tensile strength. For instance, going from grade 2 to grade 5 will allow a 60% increase in preload. Going from grade 5 to grade 8 will allow a 25% increase in preload.

Multiple fasteners

To ensure bolted joints are tight but not too tight, consider the interaction between fasteners. An extreme example is a bolted pipe flange with a gasket.

Tightening any one bolt affects the tension on all of the other bolts. The sequence of tightening will determine whether the joint leaks. It is necessary to follow the specified criss-cross tightening pattern, torque steps and tightening torque.

It is clear that a fastener should be tightened to the correct load. For a critical fastener, tightening should be done with an accurate, correctly calibrated torque wrench. That does not mean there is no margin for error. Designers always provide a safety margin, but that should be used as a safety, not taken up by careless or inaccurate tightening. When replacing fasteners, use a fastener of equal or higher grade.

Fasteners subject to large fluctuating loads are at risk of fatigue failure and, therefore, should not be re-used. That adds to the number of cycles. Even the act of loosening and re-tightening a fastener shortens its life when used in a high-fatigue application.

Bolts that break after a period of service might be because of an increase in load or a result of fatigue. In either case, it would be desirable to use stronger bolts with an appropriately higher torque or add more bolts to the joint. Another safety precaution is to buy fasteners only from reliable suppliers. Avoid using mislabeled or below-

standard fasteners. Q

Richard B. Wright is chairman of Wright Tool Co. (Barberton, OH) He can be reached at

(800) 321-2902.

Tech tips

• The amount of tension required for a bolt depends on the size and grade of the bolt, as well as the nature of the load.

• Because bolt tension is difficult to measure, bolts must be tightened to a torque.

• For bolts correctly tightened bolts that are breaking, use higher strength bolts, larger bolts or more bolts with the appropriate tightening torque for the new bolts.

• Tightening any one bolt affects the tension on all of the other bolts.