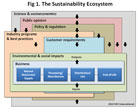

Commerce resides in a multilayered and interconnected world of sustainability. At its core, a company uses and outputs materials and energy. In doing, it causes environmental and social impacts-some good, but many detrimental. These are managed according to drivers and expectations from customers, industry norms, policy, regulation and public opinion. Ideally, the entire picture is informed by the ecological, toxicological, physical and other sciences. Source: NSF International

The United Nations’ key definition of sustainability first appeared in 1987: “Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

While it is generally understood that this means balancing complex social, economic and environmental issues, it is less clear how sustainability might be realistically achieved in the face of our existing models of growth, which are inextricably tied to natural resource extraction, production and consumption.

Ultimately, there’s a tension between sustainability for public benefit: indefinite access to high quality, abundant environmental and social goods and sustainability for commercial benefit; indefinite access to and privatization of natural resources and the availability of future markets to sell goods and services.

An example spider chart shows performance metrics for sustainability issues deter-mined to be material by a company. Each goal is established against a baseline and nor-malized to 100 regardless of the underlying unit: gallons, kWh, tons, etc. Source: NSF International

Sustainability in Context

Fortunately, a growing number of trends offer guidance for those firms embracing sustainability. Understanding these trends enables firms to make meaningful contributions, prioritize investments and create company value.From a manufacturing perspective, sustainability should be conceived of as the next logical step in the historical trend from craft, mass, flexible, to small lot production. In each case, cost was driven down by eliminating inefficiencies, waste and variation. Today, as more and more social and environmental externalities are making their way onto a company’s balance sheet, sustainable manufacturing has evolved to identify and manage those otherwise unforeseen costs of production.

Climate change is an excellent example. Until a few years ago, companies could emit carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases freely. Today, the direct cost of carbon is revealing itself through cap-and-trade, tax and other forms of regulation. But there also is an increasing indirect cost as companies experience supply, manufacturing and market insecurities from climate change itself: higher temperatures, rising sea levels, changing patterns of precipitation, and an increased frequency and severity of weather events.

Ultimately, the argument that corporations should not spend shareholders’ profits on noncore social or environmental benefits is being undermined by both the size of the risks and the opportunities a company faces. While it is not always possible to quantify exact returns, investments in funds indexed to measures of social responsibility are increasing. The financial community has started to view sustainability as a proxy, at least, for sound and progressive management. Sustainable manufacturing should be considered the primary tool to limit the impact and maximize the advantages presented by properly pricing social and environmental externalities.

Sustainability Trends

Many sustainability programs arose when organizations moved beyond legal compliance to institute management systems, particularly environmental management systems. These vehicles allow companies to effectively set and achieve objectives related to energy efficiencies, waste and water reductions, and reuse and recycling programs.While cost savings continue to be cited as factors that drive these improvements, the link between sustainability benefit, costs and return on investment is often weak. In parallel, there was a growth of social accountability, often connected to issues of corporate governance and investor relations. But there are two shifts taking place.

First, companies are using increasingly sophisticated risk analyses to identify priority factors. Coca-Cola, for example, notified shareholders in its 2003 Annual Report of the material risk represented by the over-exploitation, pollution and mismanagement of water supplies and launched a comprehensive water stewardship program. In the 2008 Annual Report, Coca-Cola had determined that climate protection had become a key component of its business strategy and was investing similarly to reduce its risk exposure.

In fact, it is common in most industries for water and climate change to rank first and second as sustainability risks.

Value Creation

The second shift is that progressive companies are beginning to recognize that the field of sustainability provides opportunities to add value beyond operational efficiencies and risk management. For example, most colleges have high numbers of students participating in campus greening initiatives while many corporate employees find internal sustainability programs to be a source of pride and engagement. It follows, then, that green companies will have an advantage over their competitors in attracting and retaining employees.Intel directly connects sustainability and employees: compensation is partly dependent on achieving corporate environmental goals. Going green, though, heightens expectations. BP’s “beyond petroleum” rebranding effort, now viewed with great skepticism, shows that the marketplace will severely test the credibility of sustainability claims.

Similarly, sustainability is on the minds of consumers although the exact mechanism by how it affects purchasing behavior is not yet fully qualified, partly because today’s economic climate has depressed market signals. We also know that the proliferation of labels and claims in the marketplace has confused, frustrated and even put off consumers. “Green-washing” or “eco-babble” has been shown to impede the take-up of what are otherwise environmentally or socially preferable products.

There are price premiums to be had, however, on a growing number of green products. Price premiums are most evident when the attribute of sustainability adds a quality to the product that can be directly enjoyed by the consumer. Baby food with organic ingredients, for example, enjoys a higher price point because an imputed health benefit is enjoyed by your child.

Conversely, it is unclear whether Subaru’s zero waste factory in Indiana allows it to charge more for its vehicles, probably because the benefits are seen to accrue to the Subaru corporation, not individual car buyers. It is certain, however, that Subaru’s manufacturing leadership has lowered costs and engendered increased loyalty on behalf of its existing customers.

In addition to differentiating products and services, the sustainability movement has opened up entirely new markets such as carbon emission mitigation technologies, clean energy, green vehicles and local food movements. Many business-to-business purchasing requirements, particularly at the government and institutional level, are mandating green products. These changes will help promote the transition to a new, green economy.

GE’s ecomagination program exemplifies the new “business of sustainability:” they are investing billions in technologies to make the world’s infrastructure more material and energy efficient-environmental and economic development fully coupled.

Steps Toward Sustainability

How can an organization increase its commitment to sustainability and make it a powerful complement to growth? First, it helps to conceptually view the entire organizational ecosystem-supply, manufacturing, distribution, product, customers-through a ‘green window’ and find opportunities for value creation.Prioritizing opportunities based on financial metrics is important, but should not be done in isolation. Vodaphone, the mobile communications firm, recently won an award for its sustainability report, Pressing Forward. Vodaphone uses two dimensions to prioritize its material sustainability issues: the degree to which an issue has current or potential impact on the company, and how important the issue is to its stakeholders. This approach demonstrates an understanding of the broad constituencies affected by the company’s operations.

After relevant sustainability issues are identified, most organizations find they can be efficiently managed by integrating them into an existing lean manufacturing culture-continual improvement, employee engagement, operations-focus, metrics-driven, supply chain management-these concepts all apply to sustainability.

Further, many sustainability programs have a strong connection to manufacturing waste and inefficiencies such as defects, wait time and over-production. Existing management systems, then, can be used to drive improvements after programs and metrics have been established, although some organizational change is required.

Often the production teams and the environmental professionals are not closely connected. Marketing, purchasing, communications and others also need to be involved. Importantly, the majority of sustainability benefits usually derive from the design stage of a process or product. After design parameters are fixed for production, further improvements are usually marginal, particularly if the use-phase of the product is added to the equation. Principles of design-for-the-environment should be considered.

Enough is known about the field of sustainability to integrate its principles into the manufacturing environment and to do so in a manner that creates value by lowering risks and costs while creating investment opportunities, improving brand equity and shaping society.

The business processes that underpin design and production are ideally suited to systematize sustainability. This is fortunate because the scale of today’s threats to the world’s ecosystems and societies present commercial risks large enough to mean the difference between continued business success and failure.

More importantly, the evolution of sustainable manufacturing will be seen as critical as we resolve the tension between sustainability for public benefit and sustainability for commercial gain in the years ahead.Q